Italy is so dense with history, art, and—most importantly—incredible food that it’s a gratifying country to simply wander guided by serendipity (and an expert travel planner) rather than an overly precise game plan. That said, themed itineraries organized around a specific artist, food, or historical period are an excellent way to both give a bit of structure and context to your meanders and discover memorable hidden spots that probably wouldn’t have made the A-list classic tour.

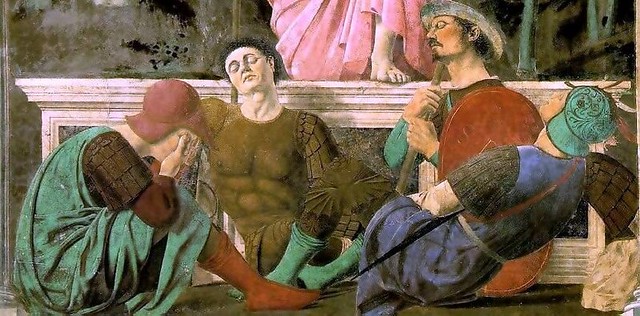

(Resurrection detail: Self portrait via Wikimedia Commons)

One favorite is the Piero della Francesca trail, winding through some of the prettiest towns on the Tuscany-Le Marche border where this Renaissance painter and mathematician lived and worked during the second half of the 1400s. Born in the Tuscan town of San Sepolcro, Piero della Francesca is considered one of the period’s most accomplished humanist painters, and his skill with both rational geometric perspective and emotive plasticity and dramatic use of light and shade made him a master still admired more than 500 years after his death.

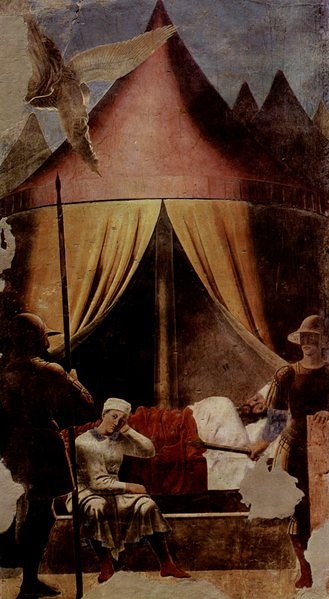

(Legend of the True Cross detail: The Dream of Constantine via Wikimedia Commons)

The trail begins at the Church of San Francesco in Arezzo, which is home to the Legend of the True Cross fresco cycle. This series of scenes, painted probably between 1447 and 1466, tells the story of the origins of the wood which was used to build the cross on which Christ was crucified and is considered Piero della Francesca’s finest (and largest) work and a masterpiece of the early Renaissance. The frescoes demonstrate the painter’s signature use of geometric symmetry and perspective, but also the influence of Flemish painters; he had returned to San Sepolcro after a year in Rome, where he had admired these artists’ skill with color and light and begun to incorporate those elements in his own works.

(Maria Maddalena via Wikimedia Commons)

The trail continues with a short walk to Arezzo’s Duomo (Cattedrale di Santi Pietro e Donato), where, immediately after completing the Legend of the True Cross, della Francesca was commissioned to paint the Maddalena. This portrait of Mary Magdalene demonstrates the artist’s complete mastery of light and shade, particularly in the saint’s drapery and the bright glass ampoule (containing unguents for Christ’s body).

From here, the trail leads to the tiny town of Monterchi, home to Piero della Francesca’s most popular work, La Madonna del Parto. Though it is now housed in a rather charmless museum, this fresco was originally located in a tiny country church, Santa Maria di Momentana. Why della Francesca would choose this obscure site to paint such a masterpiece remains a mystery, though it has been suggested that the artist was visiting the town for his mother’s funeral in 1459. An earthquake in 1785 damaged the original church, and the fresco was detached and moved to the newly restored building, now a small cemetery chapel, where it was rediscovered and identified by a visiting art historian in 1889.

(Museum of the Madonna del Parto by Sailko via Wikimedia Commons)

In 1992, the fresco was “temporarily” moved to its present museum, and a dispute began between the town and the diocese over the painting’s ownership, which continues to this day. Despite the convoluted history of this mysterious painting, the work has been one of the artists’ most beloved for centuries, as aspiring mothers-to-be have been making pilgrimages to visit and pray before the moving portrait of the pregnant Mary flanked by two exquisite angels long before the fresco was known to be a work of the Renaissance master. Still today, visitors often see women quietly supplicating the Virgin for divine assistance on their quest to have children.

(Polyptych of the Misericordia detail: Madonna della Misericordia via Wikimedia Commons)

The next stop along the Piero della Francesca trail is his hometown, San Sepolcro. Here the trail leads back in time, to the Polyptych of the Misericordia. This large alterpiece was one of the artist’s first important commissions and took seventeen years (roughtly 1445 to 1462) to complete; the 23 separate panels depict a number of saints and scenes from Christ’s life and show a fascinating evolution of della Francesca’s skill from the earliest to the final panels. Perhaps the most striking and masterful is the largest, the central Madonna della Misericordia, in which a larger-than-life Madonna stretches her mantle over her followers (coincidentally members of the confraternity which commissioned the work) in a gesture both protective and perfectly symmetrical.

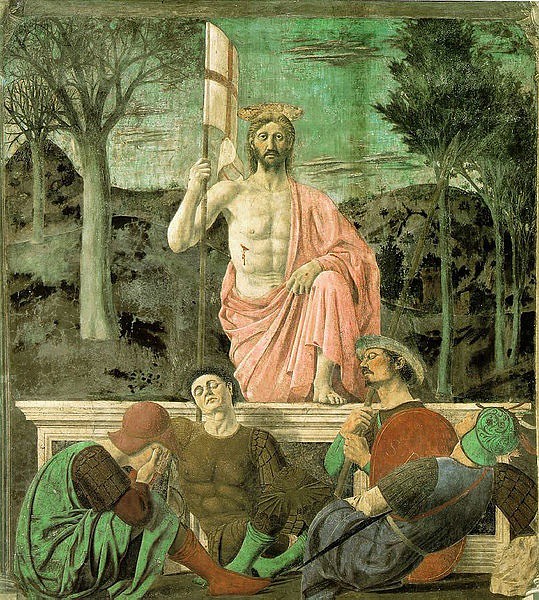

(Resurrection via Wikimedia Commons)

The same Pinacoteca Comunale which houses the Polyptych is also home to della Francesca’s exquisite Resurrezione fresco, dating from the early 1460s. This work is rich with religious and civic symbolism (the subject is an allusion to the name of the city of San Sepolcro) and intricate geometry in its composition and has been a favorite of English culture critics from Austen Henry Layard to Aldous Huxley. It was the latter’s essay describing the work as the greatest picture in the world which inspired British artillery officer Tony Clarke to refrain from shelling San Sepolcro during the Second World War, thus saving the precious fresco and becoming in the process a local hero.

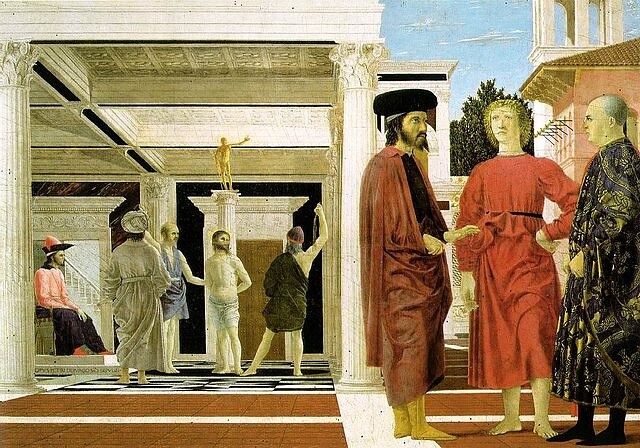

(The Flagellation of Christ via Wikimedia Commons)

From Tuscany, the Piero della Francesca trail passes into the region of Le Marche, specifically to the stoic hilltop town of Urbino where the imposing Palazzo Ducale is home to the unimposing yet greatly admired Flagellation of Christ. If this painting looks familiar, it’s probably because it is mentioned in most art history classes as one of the best examples of linear perspective—in particular, the use of a single vanishing point—and geometric composition in the history of painting.

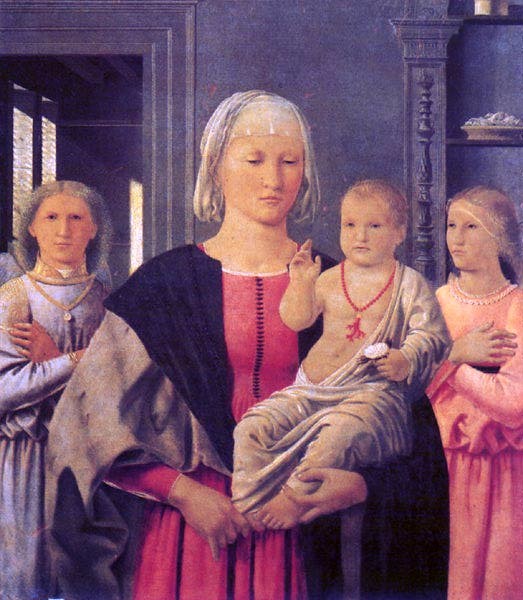

(Madonna di Senigallia via Wikimedia Commons)

The trail ends in front of della Francesca’s Madonna, also part of Galleria Nazionale’s permanent collection (it is currently on loan to Boston’s Museum of Fine Arts but is scheduled to return by the end of this month). This late work, like the Flagellation of Christ, is a masterpiece of perspective and composition, tempered with a delicate intimacy of facial expression and Flemish-inspired use of light and shade. Probably commissioned for a private chapel, the painting was moved during the First World War from Senigallia to Urbino’s Palazzo Ducale to save it from bombardments. Stolen in 1975, it was recovered (along with the Flagellation) the following year in Switzerland and has been one of the Galleria Nazionale’s crown jewels since.

If you’ve been inspired and don’t want your journey to end, other important Piero della Francesca works can be found in Perugia (Polyptych of Sant’Antonio), Florence (Portraits of the Duke and Duchess of Urbino), and Milan (Montefeltro Altarpiece). Happy trails to you!