If you think that Charlie Sheen has a corner on the bad boy-slash-artistic genius market, think again. Centuries before temperamental Hollywood actors were trashing hotel rooms and scandalizing the morally upstanding,16th century Baroque painter Caravaggio was blazing the trail of high-profile excess and brawling, a route which led from Rome to Naples to Malta to Sicily and back to Naples as he sought to keep a step ahead of the law and his personal enemies.

(Photo via Wikimedia Commons)

During his brief time in Sicily (between 1608 and 1609), Caravaggio produced three breathtaking masterpieces, emotionally fraught works reflecting the evolution of his signature chiaroscuro, a new frieze-like composition style which juxtaposed a number of figures against vast empty backgrounds, and the fragile mental state which marked the increasingly erratic and violent artist’s final years.

Caravaggio reached the Sicilian shores after a number of years on the run; his killing (perhaps unintentionally–the circumstances have been a matter of debate for centuries) of a young man led him to flee Rome in 1606 for Naples, where he could live under the protection of a powerful Neapolitan family. Shortly afterwards, he moved on to Malta, probably seeking connections that could lead to a pardon for his crime in Rome.

Though initially his move to Malta proved successful, both professionally (he received a number of important commissions upon his arrival) and personally (The Grand Master of the Knights of Malta took a particular liking to Caravaggio and inducted him into the Order), his fortunes soon took a dramatic downward turn. By 1608, he had been again arrested and was summarily expelled from the Order.

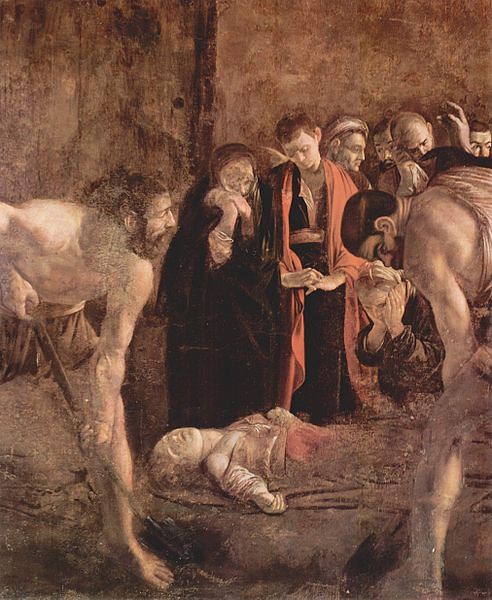

His options narrowing quickly, Caravaggio set out for Sicily where an old friend from his formative days in Rome was now living. Upon his arrival in Syracuse, he was almost immediately commissioned to execute an altarpiece for the Basilica di Santa Lucia al Sepolcro, depicting the patron saint of the city (Saint Lucy) whose remains had once been interred below the church but had been stolen during the early Middle Ages.

(Photo via Wikimedia Commons)

The Burial of Saint Lucy

The resulting Burial of Saint Lucy (now hung in the Chiesa di Santa Lucia alla Badia in Piazza Duomo) is remarkable for the artist’s mastery of the dramatic use of light and the perceptual trick of positioning two outsized figures in the foreground (the gravediggers) which creates a sense of depth otherwise difficult to render against the dark, flat background.

Though the final work shows Lucy with a slit in her neck, studies have revealed that the initial composition depicted the saint’s head completely detached, which can explain the odd position of the head thrown-back and slightly turned.

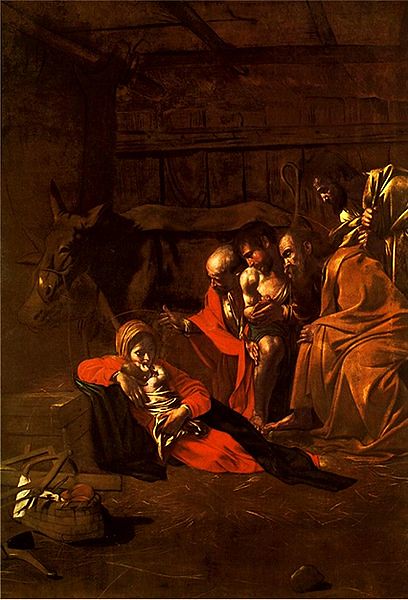

(Photo via Wikimedia Commons)

Adoration of the Shepherds

From Syracuse, Caravaggio moved on to Messina where he executed two important works. The first, the Adoration of the Shepherds (now in Messina’s Museo Regionale), was commissioned as an altarpiece for the Chiesa della Santa Maria della Concezione and was one of the highest paid works of Caravaggio’s career. Restored in 2009, the Nativity scene is remarkable for its humble depiction of the Holy family, tenderly posed on the dirt floor in a shadowy hovel of a stable.

(Photo via Wikimedia Commons)

The Raising of Lazarus

This move toward a vulnerable realism, highlighting human frailty and, perhaps, desperation culminates in The Raising of Lazarus (also in the Museo Regionale). The startling realism of this work has shocked viewers since 1609, when it was unveiled as the altarpiece of the church of the Padri Crociferi. It is believed that Caravaggio used a days-old corpse as a model for Lazarus—some say that one of the background figures can be seen holding his nose against the stench—and the dynamic interaction between the figures and dramatic diagonal of Lazarus’ Christ-like pose, all illuminated by a focused stream of light, jump out at the viewer against a sprawling empty backdrop that occupies almost half the scene.

These works are, sadly, among Caravaggio’s final paintings. Shortly after completing his Messina commissions, the artist returned to the protection of Naples’ powerful Colonna family and there painted his final works. Not even the Colonnas could save the tortured artist; in Naples an attempt was made on his life, and, during a 1610 voyage back to Rome in hopes of receiving his long-sought pardon, Caravaggio died in circumstances which remain shrouded in mystery to this day. Some believe he died of fever, some that he was murdered, and recent DNA testing on his remains (found in Porto Ercole in 2010) found high amounts of lead, leading some to conjecture that he died of lead poisoning from his own paints.

(Photo via Wikimedia Commons)

Regardless, from the unique evolution of his style that marks his Sicilian period, Caravaggio’s last works in Naples had already moved on to develop figures with more plasticity than his previous posed models and a more impressionistic brushwork. Had he lived on, chances are he would have continued revolutionizing Baroque art with the same speed that he had shown during his brief months in Sicily. But, bad boy that he was, we will never know what could have been.